Your Five-Minute Guide to Understanding Physiological Regulation

Photo by Jared Rice on Unsplash.

You’ve probably heard me and other people banging on about physiological regulation or some variation of the same thing. Any time someone is talking about the vagus nerve, the link between exercise and emotional stress, getting enough sunshine first thing in the morning, blood sugar and cognition… the list goes on but I think you get the picture: these are all examples of ways that we can work with our innate physical systems to impact our mental and physical states.

It’s called physiological regulation because physiology refers to our entire being. It refers to the interlinked nature of every system that contributes to how we feel, think, behave, and function. Let me explain this a little bit more.

In 1641, the famous French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician Decartes introduced the concept of dualism. He saw the mind and body as two separate entities, an idea that he introduced to the medical community and to wider society.

Descartes viewed our conscious experience of life purely as a product of what happens in our mind, which he saw as a nonphysical entity.

This was a very convenient idea to espouse at the time, given his interest in the body. It gave him a foundation to lobby the church to allow him to dissect corpses to better understand human anatomy because, as he argued, his work wouldn’t impact the human spirit, which the church was loathe to relinquish control over.

Remember the quote, “I think, therefore I am”? That famous line belongs to Descartes.

What this implies is that the body, which he believed couldn’t think, is merely a physical extension of our mind that has no ability to act and make decisions independently. It is completely reliant on the mind for direction and instruction as to how to move and behave.

The problem is that Descartes didn’t really have a basis for these claims. He couldn’t answer the question of why someone would perceive pain in one of their limbs when it was hurt, since the signal for pain was coming from the limb, rather than arising in the mind. He couldn’t accept that there might possibly be a bi-directional relationship between the physical body and consciousness.

In the intervening years, neuroscientists and researchers on consciousness researchers came to believe that our conscious experience is the result of neural activity that takes place in the brain. They were able to correlate specific patterns of neural activity with people’s conscious experiences in a number of cases. This lead them to assume that the brain is the source of consciousness. It’s a departure from Descartes original theory but it continues to perpetuate the belief that our body is little more than an extension of our conscious selves.

But correlation doesn’t necessarily equal causation, as any good scientist knows. Correlation is a term that we often use in science to describe a relationship between two or more phenomena that seem to have some kind of relationship but the mechanism of action is unknown. An example that’s very relevant right now would be the correlation between eating red meat and heart disease. We know that people who eat more red meat are more likely to get heart disease based on observational data but because we haven’t done the kind of experiments where every factor in a person’s diet is controlled for and made comparable, there’s not really good evidence that red meat is the cause of those people suffering more from heart disease. In fact, there’s some pretty good evidence that it’s not the causal factor and that other things are but that’s an entire post for another day.

Bringing it back to neuroscience and consciousness, just because some brain patterns were correlated with conscious experience doesn’t mean that consciousness arises in the brain.

More recently, neuroscientists have come to the conclusion that our conscious experience is actually the product of what happens in both our body and our brain.

Further research is needed to truly grasp what’s happening but the work of researchers like Antonio Damasio, Mark Solms, Evan Thompson, and others is teaching us that consciousness not only has a biological basis, but that it also arises through processes that take place in the brain and the body.

This explains observations of significant correlations between mental and physical wellbeing. For example, the now-famous ACE studies of the early 2000s showed that people who experience trauma in childhood have an increased risk of experiencing mental and emotional health issues later in life. What’s more, they are more likely than can be attributed to chance to suffer from a wide range of chronic physical conditions, such as autoimmune disease, heart disease, respiratory diseases, and cancer. It can also lead to the shortening of telomeres, meaning that children with stress tend to age faster than others. The inflammatory processes associated with stress in the brain mediate inflammatory processes in the body, which interact with a person’s genes and lifestyle to produce whatever conditions they ultimately wind up with.

At the same time, inflammatory processes that are taking place in the body have been shown to predispose an individual to develop mental health issues.

Research shows that people who go to military personnel with pre-existing low-level physical inflammation are more likely to develop post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) while on tour than those who don’t. It’s thought that their body is already primed for a response to stress, be it physical or mental, meaning that they become hyper-responders when a potentially traumatic encounter occurs.

The implications of these findings are huge for those of us working in the field of human wellbeing and health, and anyone interested in personal wellbeing. It means that the brain and body are part of an interconnected system that are in constant communication with one another.

Thoughts that occur in the brain affect what then happens in the body but the body is equally able to influence brain function and activity.

There are multiple structures linking the brain and the body but perhaps the most relevant and prominent is the central nervous system (CNS). The central nervous system is composed of bundles of nerve fibres that act as conduits for information between the brain and the body. It’s basically a messenger that gathers information from every single part of our body and relays it to the brain and vice versa. Just like the brain, it’s composed of neuron’s and axons that use neurotransmitters to communicate. The signals that the CNS sends and receives determine our response to stimulus at a local level and at a wider physiological level.

For example, without our CNS, we wouldn’t know when a pin pricking our finger pierces the skin, causing pain or be able to coordinate to move our hand away from the pin. We might experience some kind of local reaction to the pain in the form of swelling and redness (part of our innate inflammatory response mediated by outposts of the CNS) but the brain would never get the message needed to change our behaviour (moving our hand). Likewise, as Bessel Van der Kolk points out in The Body Keeps the Score, people with physical dissociation (a state in which their physical experience is disconnected with their mental experience that arises through traumatic or stressful experiences), tend to struggle to coordinate their movements and experience clumsiness. It’s likely due to impairments in CNS functioning that prevent their mind and body from being to able to communicate optimally.

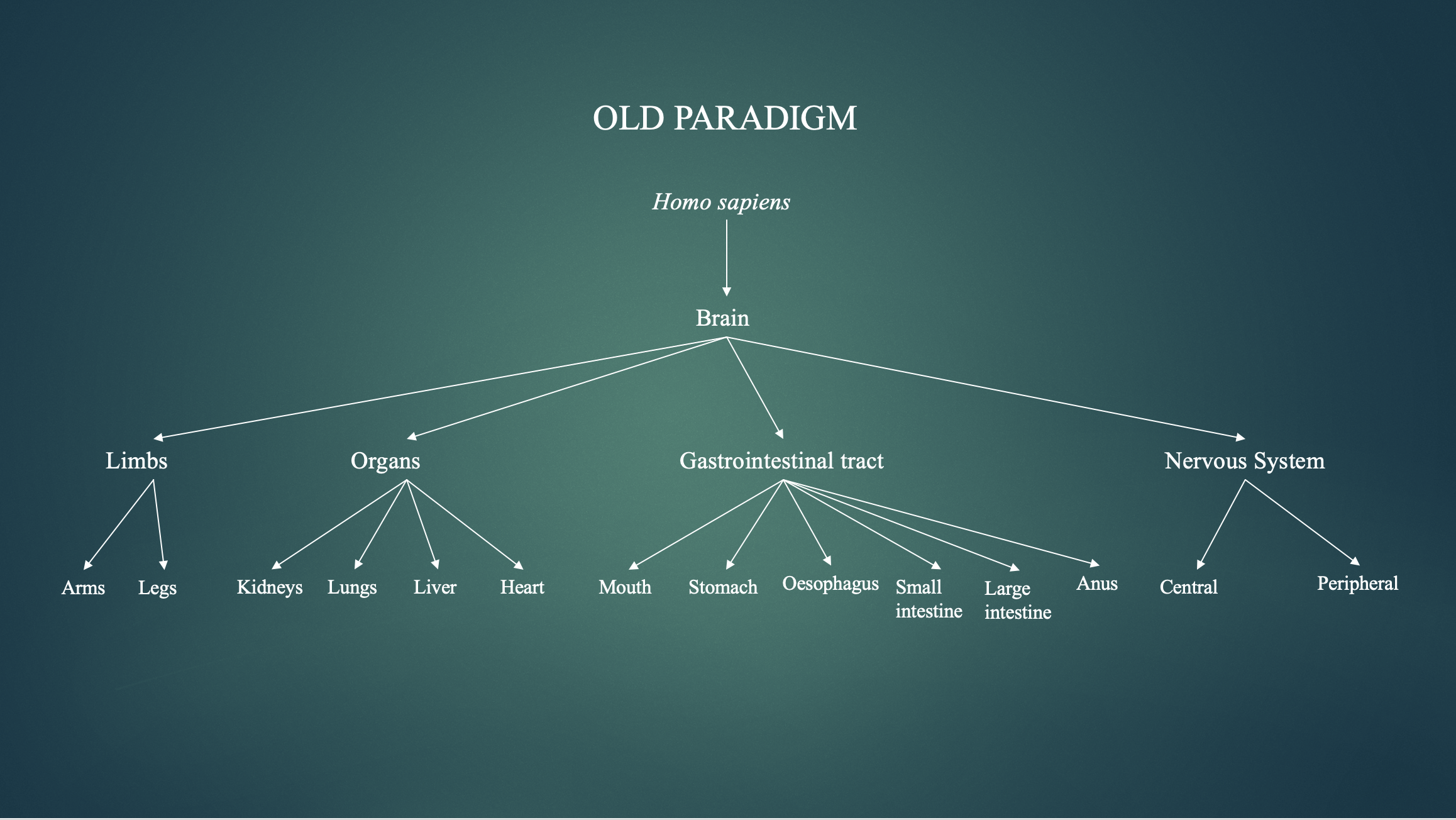

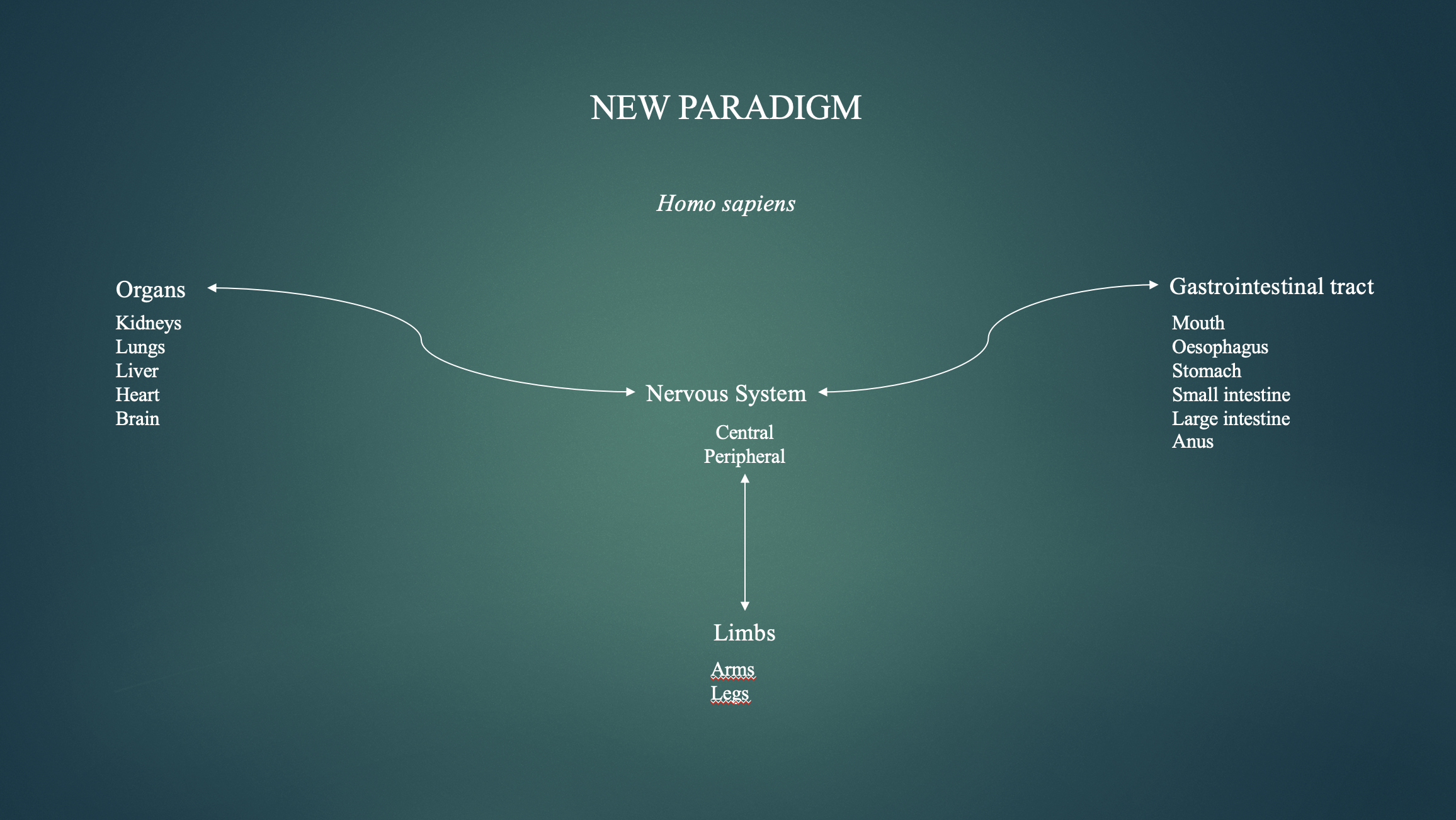

Below are two diagrams that outline the old way of thinking and the new.

The digram that depicts the old way of thinking about brain-body interactions is hierarchical, meaning that all thought and behaviour is believed to arise from brain activity. There is no feedback from the body to the brain.

The newer perspective shows that thought and behaviour is the product of the combined experience of brain and body, taking place on a more horizontal axis.

As you can see, the nervous system provides connectivity between our organs, limbs, and gastrointestinal tract. This is a really simple model but it gives you the idea: everything in our body is interconnected via the nervous system, giving rise to our physiological state.

What’s more, we’re beginning to understand how changing our physiology via changing the signals that the CNS sends to both the brain and the body can change wellbeing outcomes. Currently, the most well-known and well-researched method of doing this is via the vagus nerve. The science of the vagus nerve and how to modulate it is a topic for a whole post of its own (or you can attend one of my in-depth workshops on it), but I hope that by now, you’ve started to understand how our conscious experience is produced by both the brain and the body.

I also want you to take this message away with you: the more that you can understand about the role that the central nervous systems plays as a messenger between all of the different parts of our physical being, the more you will be able to change your physiology and health outcomes.

Change your physiology and you can change your life.